Introduction

We are living in the golden age of easy. Tap a button, get a ride. Tap another, dinner is at your doorstep. Missed a show? Stream it anytime. Forgot to buy socks? Don’t worry! There is a monthly subscription that will deliver them, pre-matched and mood-themed. In this modern orchestra of automation, effort is the only note that sounds off-key.

Convenience is no longer a perk. It is the product. We now subscribe to everything: music, meals, meditation, even relationships (depending on how loosely you define commitment apps). We have outsourced not just chores, but choices. Why bother thinking about what to cook, what to wear, or how to entertain yourself, when someone (or something) can do it for you for a monthly fee?

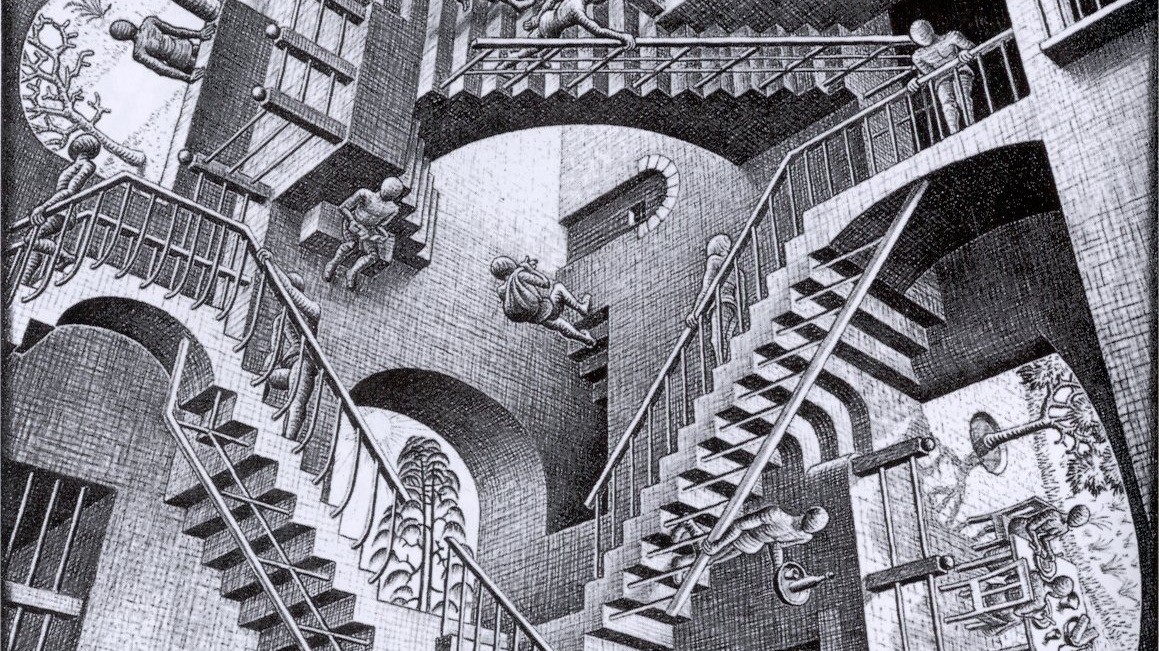

On paper, this seems like utopia with fewer errands and more freedom. But philosophically, it poses a quiet threat: if everything becomes frictionless, when do we develop calluses? We have grown so used to smooth surfaces, we have forgotten the rugged texture of real life. The messy, meaningful bits that require attention, effort, patience and even boredom.

The modern gospel says: “Don’t own. Don’t commit. Just rent, return, repeat.” But what happens when we start treating people, places, and communities like transient subscriptions too?

This blog is not a rant against technology. It is a reflection on what we are trading in exchange for ease: ownership, belonging, shared effort, and meaning. And how a little friction might actually be good for the soul.

1. What Is the Endowment Effect?

The endowment effect is a behavioral economics principle that suggests we place more value on things simply because we own them. First identified by Richard Thaler, this cognitive bias breaks the basic rules of classical economics, which assumes humans make rational decisions based purely on utility and market value.

According to the endowment effect ownership itself creates emotional value, making us unwilling to trade, sell, or part with an item, even when offered something objectively better.

Now, think about a toddler with a favorite blanket or toy. It doesn’t matter if there are five other identical stuffed bears in the room; they want that one. The raggedy, drool-stained bear they’ve had since infancy. Try swapping it out and you’ll be met with tears, tantrums, and a lesson in early-stage possessive psychology.

“We do not love people and things because they are valuable. They become valuable because we love them.” — Friedrich Nietzsche

Psychologically, the endowment effect stems from a few sources. One is loss aversion: we dislike losing what we already have more than we enjoy gaining something new. Another is identity attachment: our possessions subtly become extensions of ourselves. Thus selling a car you have had for years feels strangely personal, or why decluttering your closet is an emotional minefield.

In short, we don’t just own things. We embed meaning into them. Lets explore what happens when our sense of ownership is slowly being replaced by access and nothing feels truly ours anymore.

2. Subscription over Ownership: The Emotional Disconnect

Once upon a time, ownership was a symbol of elite status. Only the wealthy owned homes, cars, libraries, or land. Everyone else rented, borrowed, or shared. But as society industrialized and wealth began to disperse, ownership became more accessible. The middle class could buy homes, build collections, and pass things down generations. To own something was to signal stability, autonomy, even legacy.

But then, the pendulum swung again. Somewhere between Netflix and Uber, we began to prefer access over ownership. Why buy a DVD when you can stream any movie, anytime? Why own a car when you can summon one with an app? Why clutter your life with stuff when you can subscribe to experiences, services, and digital replacements?

In the past, we didn’t just trade objects, we traded emotional investment. Today’s subscription culture may be practical, but it is emotionally transient. When everything is rented, nothing feels like yours. There is no attachment to the furniture in your rented flat, the playlist you don’t technically own, or the e-book you can’t lend to a friend. You use it, you enjoy it, and when it disappears, you scroll for a replacement.

“Ownership is not just about possession. It’s about the illusion of permanence.” — Daniel Kahneman

The endowment effect thrives on permanence. It is hard to feel emotionally attached to a Netflix series you binge in one weekend and forget the next. There is no tactile memory, no patina of time. It’s all efficient but eerily forgettable.

This shift has subtle consequences. When we stop investing in the objects around us, we may also stop investing in the places and people connected to them. If everything can be swapped or upgraded, why bother forming bonds? Why take care of anything?

Access culture might save us from clutter, but it also distances us from meaning. It is not about the thing itself; it is about how it makes us feel. And feelings, unlike subscriptions, can’t be paused or renewed.

3. The Erosion of Community and the Illusion of Convenience

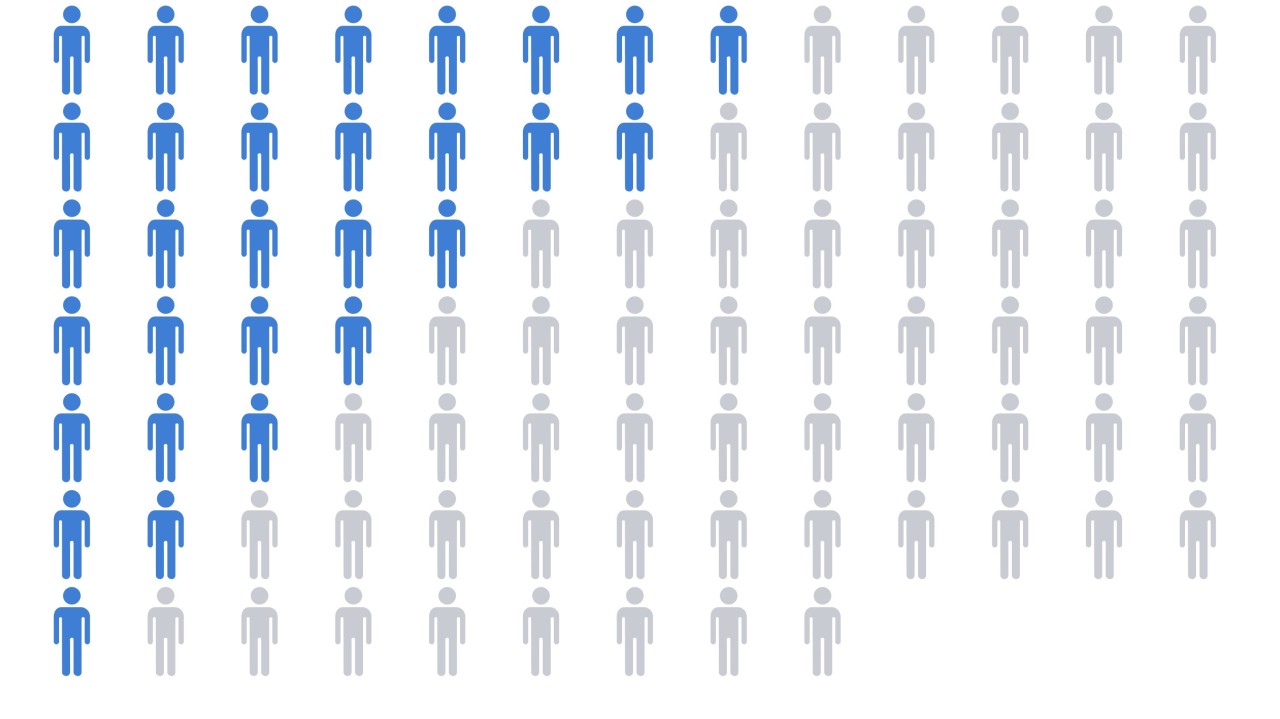

Before industrialisation, life was deeply communal. Families weren’t nuclear. Instead, they were multi-generational units, often living under one roof or in close proximity. Resources were shared, responsibilities rotated, and the village market wasn’t just a place to buy. It was a place to meet, chat, exchange recipes, gossip, and build bonds. A tomato wasn’t just a tomato; it came with a story, a smile, and probably a discount if your grandmother was friends with the seller.

Then came the factories, the railroads, the time clocks. People moved to cities, drawn by jobs and promises of a better life. Homes got smaller. Families fragmented. The weekly market became a supermarket. The neighbour became a stranger behind a closed door. Efficiency replaced intimacy.

Modern consumerism fractured the community and then sold us back the illusion of it. We are now willing to pay a premium for the very convenience that disconnected us in the first place.

Fast forward to today: our apps are trying desperately to recreate what was once organically ours. Your grocery app might tell you the name of the farmer or the origin of your eggs. But let’s be honest, it is a simulation of the real connection that is now lost.

Added in pastel-coloured UI are slogans to create belongingness: “Buy from small businesses,” “support local sellers,” or “shop consciously” all sneakily designed for you to buy more.

“We create our own monsters and then market them as miracles.” — Unknown

Convenience is now the gold standard. But convenience is isolating. It removes friction but also removes interaction. No need to ask a neighbor, wait in line, or talk to a human. Tap, pay, receive. Simple. Solitary.

What we lost in that trade wasn’t just inconvenience. It was community, shared effort, and the subtle joy of being part of something larger than oneself.

4. The Convenience Trap: Comfort as a Drug

There was a time when getting milk meant putting on shoes, walking to the grocery store, maybe exchanging a few words with the cashier, and hauling the bag back home. Mundane? Maybe. But it was also normal an everyday task with a sprinkle of human interaction.

Then came the delivery apps. Suddenly, milk arrived at your doorstep within 20 minutes for free. Funded by VC billions and operating at a loss, these platforms created a fantasy world where effort was optional and waiting was a crime. Consumers got used to it. Addicted, even. And now, as these services begin charging delivery fees in the pursuit of actual sustainability, people feel betrayed. As if something they were never really paying for has been unfairly taken away.

“Comfort is a drug. Once you get used to it, it becomes addicting. Give a weak man everything he wants, and he will destroy himself.” — Carl Jung (attributed)

The deeper problem? We have built an entire culture around expecting ease, and it has quietly eroded our resilience. The slightest friction like traffic, queues, delivery delays or an app outage feels like injustice. We measure satisfaction not by value, but by how little we had to try. The benchmark for what counts as “fair” has shifted dangerously close to “effortless.”

Convenience, once a luxury, is now a baseline expectation. And when comfort becomes the default, discomfort feels like a personal attack. We aren’t just outsourcing chores. We are outsourcing our capacity to cope. Our ability to navigate life’s inevitable rough patches is dulled by our dependence on smooth surfaces.

In chasing ease at every turn, we may be losing the emotional muscle memory that once helped us adapt, tolerate, and grow. Because real life is messy, unpredictable and imperfect. It can’t always be ordered in 10-minute delivery slots.

Conclusion

Let’s be clear, chasing ease is not inherently bad. In fact, it has given us some of the greatest inventions of our time like modern medicine, public transport, the internet etc. These are marvels of convenience that uplift entire communities, streamline human potential, and create access where none existed. When thoughtfully designed, convenience is not a shortcut but a bridge.

The problem begins when ease becomes the product itself; marketed not as a tool for collective good, but as a means to maximize individual comfort at any cost. That is when the impact begins to twist. The shared becomes siloed. The meaningful becomes mechanical. The system that once promised connection starts to reward isolation. We stop asking: Who else benefits from this? and start asking: What is in it for me?

And this is where the disintegration starts.

What we really need to reclaim is not stuff but meaning, effort, and shared purpose. The antidote to passive consumption is active contribution. Real fulfillment doesn’t come from the fastest delivery or most optimized schedule. It comes from showing up, trying, building and giving.

“We make a living by what we get, but we make a life by what we give.” — Winston Churchill

Because true freedom doesn’t come from removing all effort. It comes from choosing where to direct it. And meaning? That doesn’t live in an algorithm. It lives in your mind, your relationships, and your willingness to care.

Effort is not the enemy. It is the seed of all things worthwhile like belonging, growth, connection, and contribution. So perhaps it is time we stop upgrading our subscriptions and start upgrading our values.

After all, belonging isn’t a service plan. It is a human one.